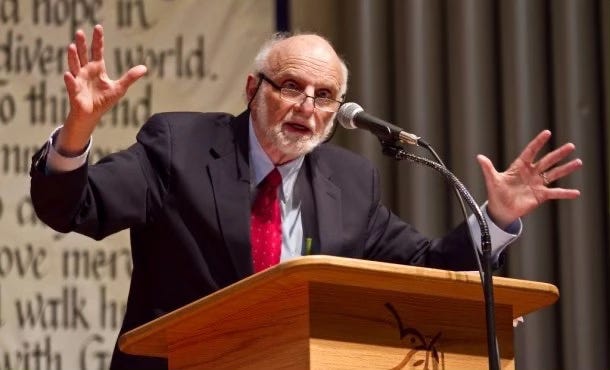

Last week Walter Brueggemann, one of the most influential people who shaped my theology died. This post, compiled from posts I have written over the last 30 years since I first came across his writing is in honour of his life and incredible ministry.

The first of his books that deeply impacted me was Living Toward a Vision: Biblical Reflections on Shalom, later republished as Peace . It was more influential than Prophetic Imagination, his best known book, perhaps because I read it shortly after coming back from Africa and my adventures with Mercy Ships. I was struggling with the narrow confines of my evangelical theology, and it was Walter Brueggemann who showed me the way forward.

He identifies the word shalom as the biblical word that best describes a vision of an all-embracing faith. He explains that the original meaning of shalom was far more than the usual English translation peace. Wholeness or completeness are better translations, but even these words are inadequate. In essence shalom is far more than the absence of conflict or even the existence of “inner peace”.

“Shalom is the substance of the Biblical vision of one community embracing all creation. It refers to all those resources and factors which make communal harmony joyous and effective.”

It embraces God’s desire to restore every part of creation and all aspects of life to the wholeness and harmony of relationship that was broken through the disruption of the Fall. Wow. That is the most wonderfully challenging description of what God intends for future and it soon had me redirecting my life towards concerns for justice, equality and care of God’s good creation.

A few years later I read Sabbath As Resistance. Talk about stimulating, challenging and encouraging. Once again it stretched, and reshaped my faith. Here, Brueggemann reminds us that Sabbath is not about keeping rules but rather about becoming a whole person in the midst of a restored, whole society.

Brueggemann contrasts the restless anxiety of our producer/consumer culture with the restfulness of God’s Sabbath world.

In our own contemporary context of the rat race of anxiety, the celebration of Sabbath is an act of both resistance and alternative. It is resistance because it is a visible insistence that our lives are not defined by the production and consumption of commodity goods. Such an act of resistance requires enormous intentionality and communal reinforcement amid the barrage of seductive pressures from the insatiable insistences of the market, with its intrusion into every part of our life from the family to the national budget….

But Sabbath is not only resistance it is alternative. It is an alternative to the demanding, chattering, pervasive presence of advertising and its great liturgical claim of professional sports that devour all our “rest time.” The alternative on offer is the awareness and practice of the claim that we are situated on the receiving end end of the gifts of God. (preface xiv)

Brueggemann explains that the command to keep Sabbath is the pivotal point of the ten commandments. The weekly work pause breaks the production cycle. It breaks the anxiety cycle and it invites us into a radical world of neighbourliness and equality. The commandments that follow he tells us really show us what neighbourliness looks like – you do not dishonour mother and father, you do not kill, commit adultery, steal, bear false witness or covet.

Sabbath is not simply a pause. It is an occasion for reimagining all of social life away from coercion and competition to compassionate solidarity. Such solidarity is imaginable and capable of performance only when the drivenness of of acquisitiveness is broken. Sabbath is not simply the pause that refreshes. It is the pause that transforms. Whereas Israelites are always tempted to acquisitiveness, Sabbath is an invitation to receptivity, an acknowledgement that what is needed is given and need not be seized. (45)

Grappling with Brueggemann’s theological interpretation occupied a lot of my mind in the next few months as I grappled with its implications for my life. I had long felt that God’s kingdom of wholeness and restfulness was the worldview around which my life should revolve but I must confess it was not always my focus. Like the Israelites and like many of us, anxiety and acquisitiveness very quickly took over and in the midst of that anxiety the temptation to let go of Sabbath and God’s vision for wholeness and completeness for all was huge.

The next step in my journey with Brueggemann was Journey to the Common Good which grew out of his Laing Lectures at Regent College.

Brueggemann talked about the Exodus story as a journey from a culture of anxiety to a practice of neighbourliness drawing parallels with our own cultures and the challenges we face.

The great crisis among us is the crisis of “the common good,” the sense of community solidarity that binds all in a common destiny – haves and have nots, the rich and the poor. We face a croisis about the common good because there are powerful forces at work among us to resist the common good, to violate community solidarity, and to deny a common destiny. Mature people, at their best, are people who are committed to the common good that reaches beyond private interest, transcends sectarian commitments and offers human solidarity. (p1)

Brueggemann presented a very different view of the Joseph story than the one we usually hold to. He points out that Joseph solidified Pharaoh’s power and enslaved the people, manipulating the economy to concentrate wealth and power in the hands of a few. The situation deteriorates and God intervenes.

The practice of exploitation, fear and suffering produces a decisive moment in human history. This dramatic turn away from aggressive centralized power and a food monopoly features a fresh divine resolve for an alternative possibility.

This divine alternative comes into being through Moses’ dream of a people no longer exploited or suffering but living in the abundance of shared generosity which is the centre of YHWH’s dream. Brueggeman very helpfully contrasts this to Pharaoh’s dream, a nightmarish dream of scarcity which precipitated the crisis encouraging Abraham and others like him to seek the security of food in Egypt even if it meant slavery.

The bread of the wilderness, the bread that God gives us to eat, is a very different sort of bread. It is the bread of YHWH’s generosity,

a gift of abundance that breaks the deathly pattern of anxiety, fear, greed and anger, a miracle that always surprises because it is beyond our capacity of expectation.

Brueggemann points out that is this bread that fills the Israelites as they stand at Mt Sinai to receive God’s commands, commands that voice God’s dream of a neighbourhood and God’s intention for a society grounded in the common good.

The exploitative system of Pharaoh believed that it always needed more and was always entitled to more – more bricks, more control, more territory, more oil – until it had everything. But of course one cannot order a neighbourhood that way, because such practices and such assumptions generate only fear and competition that make the common good impossible Such greed is prohibited by YHWh’s kingdom of generosity. (25)

This is a challenging and thought provoking book that reminded me of how easily I seek my own good over the common good and how frequently I need to be challenged afresh with the values and principles of God’s new society. Our God is a generous God – not to me as an individual for the accumulation of personal wealth, but to us as a society of God’s people. This type of generosity must be shared, it must seek the common good and it must work for the welfare of all.

Brueggemann’s books continue to influence me and hopefully keep me journeying in the right direction and I am sure they will continue to do so for the rest of my life. His Lenten devotional A Way Other Than Our Own and his Advent devotional Celebrating Abundance are ones I return to year after year.

Brueggemann’s influence will not end with his death and my prayer is that all of us will continue to read, and re-read his books allowing them to challenge and reshape us for the rest of our lives.